Develop a community-based primary healthcare system

The current PHC system is fragmented with a lack of overall strategic planning and co-ordination on service development and vertical and horizontal integration. Fragmentation in the health system results in inefficiencies and misalignment with the use of resources. The Government recognises the need to establish a more systematic and coherent platform to incentivise the community to manage their own health, promote awareness of the importance of PHC services and improve service accessibility. With the continuous development of District Health Centres (DHCs) across the territory, the PHC service delivery model in Hong Kong will gradually evolve into a district-based family-centric community health system. Efforts are made with a view to triggering a paradigm shift in the present healthcare system and people’s mindset from treatment-oriented to prevention-oriented.

In 1978, The World Health Organisation (WHO) passed The Declaration of Alma Ata, which recognises PHC as the key to "Health for All" [14]. This declaration sets the scene for international efforts to promote PHC and formally acknowledges the pivotal role of a robust PHC system.

As discussed in Chapter 1, in the recent decades, Hong Kong and other countries in the world alike are facing similar healthcare challenges: ageing population, increase in chronic disease prevalence, increase in healthcare demand, decrease in elderly support ratio, more complex health needs, inadequate healthcare manpower and financial resources, and growing public discontent towards healthcare in both quality and quantity. The latest report of the Global Burden of Diseases reveals that, from 1990 to 2019, the cause of disease burden has shifted from communicable diseases to chronic diseases. It also correlates with broader determinants of health, such as people’s income, education level and population structure [15].

To address these challenges, a new shift of focus from life-saving treatments to the prevention of chronic diseases with whole-of-society co-ordinated effort is needed. According to the WHO, evidence has shown that PHC is the most equitable, efficient and effective strategy to enhance the health of populations. In addition, there is considerable evidence that health systems based on PHC services have better health outcomes [16]. A brief introduction on the latest planning of PHC in five selected places, namely, Mainland China, United Kingdom, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand is set out in Appendix B.

Primary Healthcare Development in Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the development of PHC could be traced back to 1990 with the report entitled "Health for all, the way ahead: Report of the Working Party on Primary Health Care". As indicated in the Report, PHC is the first point of contact for individuals and families in a continuing healthcare process which entails the provision of accessible, comprehensive, continuing, co-ordinated and person-centred care in the context of family and community [17]. The Report comprehensively reviewed the development and challenges of healthcare services in Hong Kong and the worldwide development of PHC as the strategy to achieving WHO member-states’ target of “health for all” and recommended a host of strategies focusing on PHC, many of which are still being adopted today.

The Report has guided the development of the later policy and consultation documents for the development of PHC and many of its recommendations are still being adopted today. In the subsequent years, a number of consultation documents released by the Government, including the “Your Health Your Life-Consultation Document on Healthcare Reform” in 2008 and the “Our Partner for Better Health – Primary Care Development in Hong Kong: Strategy Document” in 2010, have all reaffirmed the need to shift from secondary to PHC as the direction of healthcare reform. An introduction of the development of PHC in Hong Kong is set out in Appendix C.

Over the years, the Government has been providing publicly-funded PHC services mainly through direct services of DH and HA. It also subsidises non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in providing PHC and social services. In recent years, the Government has launched various government-subsidised or public-private partnership (PPP) healthcare programmes as recommended in previous healthcare reform consultation documents with a view to tapping into the private healthcare sector resources in meeting public PHC service demand and enhancing the quality of health of the population and healthcare services for them. These include the Vaccination Subsidy Scheme (VSS) since 2008, Elderly Health Care Voucher (EHCV) Scheme since 2009, General Out-Patient Clinic PPP Scheme (GOPC PPP) since 2014, and Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme since 2016. Together these subsidised programmes accounted for some $3 billion government fixed expenditure on PHC in 2019/20.

The Department of Health

DH is the Government’s health adviser and agency to execute healthcare policies and statutory functions. It safeguards the community’s health through a range of promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative services. Healthcare services are being delivered using a life course approach through DH’s various areas of work with emphasis on preventive care. The key healthcare functions of DH are in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1

DH’s Key Healthcare Functions

Oral Health Education Division;

Special Preventive Programme

- Health promotional activities and programmes that target both the population at large and also specific groups

(Communicable Disease Branch; Non-communicable Disease Branch; Emergency Response and Programme Management Branch; Public Health Services Branch; Infection Control Branch; Public Health Laboratory Services Branch; Specialised Services Branch; Health Administration and Planning Office)

- Prevention and control of both communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are executed through surveillance, outbreak management, health promotion, risk communication, emergency preparedness and contingency planning, infection control, laboratory services, specialised treatment and care services, training and research (including surveys)

- Disease prevention programmes, including vaccination programmes and cancer screening programmes

Family Health Service;

Student Health Service;

Elderly Health Branch;

School Dental Care Service

- Health promotion and provision of preventive care to individuals of specific age groups and/or carers

- Immunisation, screening of congenital diseases, growth monitoring and developmental assessment, and health assessment for population groups including children, primary and secondary school students, women, elderly; and dental check-up for primary school children

- Ante/postnatal care and family planning service for child bearing age women, cervical screening services, diagnostic and counselling for genetic diseases, primary healthcare services including chronic and episodic disease management for the elderly

- Implementation of the Elderly Health Care Voucher Scheme

- Promotion of a tobacco-free culture and co-ordination of smoking cessation services

- Assessment and rehabilitation plan formulation to enable children to overcome developmental problems

- Medical care and health promotion for the prevention and management of sexually transmitted diseases and skin diseases

- Medical care and health promotion for the prevention and management of sexually transmitted diseases, viral hepatitis and HIV/AIDS

- Medical care and health promotion for the prevention and management of tuberculosis and respiratory diseases

Apart from direct services, DH also runs disease prevention programmes by way of PPP, including programmes for vaccination (such as the Government Vaccination Programme and the Residential Care Home Vaccination Programme that provide seasonal influenza vaccination and pneumococcal vaccination for elderly living in the community and residential care homes), cancer screening (such as colorectal cancer screening programmes) and smoking cessation.

Hospital Authority

HA, established under the Hospital Authority Ordinance (Cap. 113) in 1990, provides public hospital and related services. It offers medical treatment and rehabilitation services through hospitals, SOPCs, GOPCs, outreach services and Chinese Medicine Clinics cum Training and Research Centres (CMCTRs). They are organised into seven clusters that altogether serve the whole city. In parallel, HA has provided a range of PHC services, including the general out-patient services, multi-disciplinary services, chronic disease management programmes including risk assessment and management programme (RAMP), nurse and allied health clinics (NAHCs) and community nursing services (CNS).

In line with the Government's healthcare reform proposals, since 2008, HA has launched a range of PPP programmes with designated one-off funding from the Government. In 2016, a dedicated endowment fund, the HA PPP Fund, was set up to allow HA to generate investment returns for regularising and enhancing ongoing clinical PPP programmes, as well as for developing new clinical PPP programmes. Among the existing PPP programmes, several of them are PHC- focused, most notably the GOPC PPP launched in 2014 and patient empowerment programme (PEP) launched in 2010. It provides patients with HT and/or DM but in stable clinical conditions a choice to receive subsidised treatment provided by private doctors.

A brief summary of the key PHC functions of HA is in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2

HA’s Key PHC Functions

- Multi-disciplinary teams of healthcare professionals are set up at selected GOPCs of HA in all clusters to provide structured risk assessment and targeted interventions for patients with DM and HT, so that they can receive appropriate preventive and follow-up care.

- NAHC comprising of nurses and allied health professionals have been established in selected GOPCs in all clusters to provide more focused care for high-risk chronic disease patients, targeting those who require specific healthcare services and those with health problems or complications. These services include fall prevention, handling of chronic respiratory problems, wound care, continence care and drug compliance.

- A PEP was implemented in all HA clusters in collaboration with NGOs. They aimed to improve chronic disease patients' knowledge of their diseases and enhance their self-management skills.

- A multi-disciplinary team from HA developed appropriate teaching materials and aided for common chronic diseases (for example, HT, DM, etc.), and provided training for frontline staff of the participating NGOs organising the PEP.

- With gradual setting up of DHCs/DHC Expresses in different districts, collaboration between DHCs/DHC Expresses and HA has been put in place for patients with HT and/or DM under the care of HA for patient empowerment and better support in the community.

- The general out-patient services provided by HA are open to all population groups with major service users being the elderly, the low-income and the chronically ill patients. Patients under the care of GOPCs comprise two major categories: chronic disease patients, such as patients with DM or HT; and episodic disease patients with relatively mild symptoms.

- HA expanded the service capacity in (GOPCs) by increasing the quota over the years and launching the GOPC PPP in 2014. GOPC PPP provides patients with HT and/or DM (with or without hyperlipidemia) but in a stable clinical condition a choice to receive subsidised treatment provided by private doctors.

- To tie in with the government’s PHC development strategy, HA has been actively planning for the development of CHCs in various districts. With an aim to provide integrated and comprehensive PHC services, the CHCs provide medical consultation, multi-disciplinary services to complement doctors’ management and control disease deterioration, as well as patient empowerment to encourage self-care.

- CNS provides nursing care and treatment for patients in their own homes. Through home visits, Community Nurses administer proper nursing care to patients and, at the same time, imbue patients and their families with knowledge on health promotion and disease prevention. The ultimate goal of CNS is to provide continuous care for patients who have been discharged from hospitals and allow them to recover in their own home environment.

- CMCTRs, with one established in each district, operate on a tripartite collaboration model involving HA, an NGO and a university. The NGOs are responsible for the running and day-to-day operation of the CMCTRs. In addition to non-subsidised out-patient Chinese medicine services, training and research functions, the CMCTRs have been providing Government-subsidised Chinese medicine out-patient services since March 2020.

Social Services Sector

With the combined effect of an ageing population and increasing longevity, the Government has been introducing various measures on elderly services mainly under the Labour and Welfare Bureau (LWB) and administered by the Social Welfare Department (SWD) with a view to promoting “active ageing” while taking care of the service needs of frail elderly persons. In terms of community-based services, SWD oversees a number of community support services, such as District Elderly Community Centres (DECCs) and Neighbourhood Elderly Centres (NECs). Although the purpose of these centres are not primarily health-focused, the medical and social need of elderly is often intertwined. For instance, DECCs and NECs invite the visiting health teams (VHTs) of the Elderly Health Service of DH in organising health education talks on different topics, such as disease prevention, nutrition and balanced diet, and organise group activities on physical exercises which aim at promoting a healthy lifestyle.

The Challenges

Respective Government bodies overseeing health and social policies (i.e. HA, DH and SWD) have been working in tandem to offer PHC services, via PPP as appropriate, while performing their respective functions. They have been complementing and facilitating implementation of the Government's public health policies through collaboration and service referrals at different levels to serve the public. Different units at DH that provide PHC services, such as Maternal and Child Health Centres (MCHCs), Woman Health Centres (WHCs), Student Health Service Centres and Elderly Health Centres (EHCs), refer their patients to the SOPCs of HA for follow-up treatment according to their needs. HA also supports the programmes of DH (e.g. the Government Vaccination Programme) where appropriate. Similarly, the SWD units which provide some PHC services, such as DECCs and NECs will also take on cases referred by HA for community support, such as those elderly patients who have been discharged from hospitals and carry a higher risk of unplanned re-admission.

Nonetheless, the current PHC system is still fragmented with a lack of overall strategic planning and co-ordination on service development. We recognise the need for synchronising and consolidating various PHC services, including those introduced and operated by different parties over time. There is much room for further integration and streamlining on both horizontally among PHC service providers and vertically between primary and secondary/tertiary healthcare sector.

Our Aim

The Government recognises the need to establish a more systematic and coherent platform to incentivise the community to manage their own health, promote awareness of the importance of PHC services and improve service accessibility. For the sustainable development of the PHC system in Hong Kong, we see the need to strengthen planning and co-ordination of resources. We also need to improve service efficiency and effectiveness by leveraging on both public and private PHC services resources.

Besides, with the reaffirmed positioning of Chinese medicine (CM) in the development of the healthcare system in Hong Kong in the 2018 Policy Address, a combination of defined Government-subsidized CM services has been provided/are to be provided at the level of primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare. CM, which emphasizes a holistic approach to understand life and provide holistic care of patient, together with the prime concept of preventive treatment of disease (including elements of prevention, care and health maintenance, etc.), should play a more significant role in the PHC system, leveraging on its strategic advantage and expertise. Multi-disciplinary collaboration should be explored to achieve better synergy effect.

With the continuous development of DHCs across the territory, we aim to shift from our current PHC delivery model into an integrated and co-ordinated district-based family-centric community health system, with accessible referral channels and clear patient pathway that connect service providers across the healthcare continuum.

In view of the above, we propose the following –

Recommendation 2.1

Develop a district-based family-centric community health system

To strengthen collaboration between the health and social care sectors and public-private partnership in a district setting, with a view to enhancing public awareness in disease prevention and self-health management, offering greater support for patients with chronic diseases, and relieving the pressure on specialist and hospital services, the Government is committed to enhancing district-based PHC services by setting up DHCs throughout the territory progressively since 2019. Through district-based services, public-private partnership and medical-social collaboration, the DHC is a brand new service model and will be a key component of the public healthcare system. The establishment of DHCs is a key step in a bid to shift the emphasis of the present healthcare system and people’s mindset from treatment-oriented to prevention-oriented. A summary of the existing service model of DHC is at Table 2.3.

With the establishment of DHCs across the territory, DHCs will progressively strengthen their role as the co-ordinator of community PHC services and case manager to support PHC doctors on one hand, and their role as district healthcare services and resource hub that connect the public and private services provided by different sectors in the community on the other hand, thereby re-defining the relationship among public and private healthcare services; as well as PHC and social service providers.

Table 2.3

Existing Service Model of District Health Centres

Existing Service Model of District Health Centres (DHC)

- Anchor of a new district-based healthcare model which leverages on public-private partnership and medical-social collaboration. It provides better primary healthcare service and co-ordination in the community

- A service network developed through partnership with organisations and healthcare personnels on the district level to support PHC doctors and enhance service accessibility and co-ordination

The top four prevalent chronic diseases and health conditions in Hong Kong:

- obesity and overweight

- hypertension

- diabetes mellitus

- musculoskeletal diseases

- One DHC in each district operated by a non-government entity

- Each DHC Operator is required to operate a Core Centre and Satellite Centres, employ a Core Team and build a DHC Service Providers Network

- It collaborates with non-government organisations in the community as partners to enhance the local support network

- A Core Team of staff is employed by the DHC Operator which consists of an executive director, chief care co-ordinator, care co-ordinators, dietitian, pharmacist, physiotherapist (PT), occupational therapist (OT), social worker and administration, information technology and finance personnel

- The DHC Operator is required to establish a district service network consisting of doctors, Chinese medicine practitioners and allied health professionals (such as PT, OT, optometrist, dietitian) within or adjacent to the district through service agreements. These network service providers will receive referrals from the DHC for providing subsidised services to members, or make referrals to the DHC

- Individual who is a holder of the Hong Kong Identity Card

- Living or working in the district

- Agree to enroll in the Electronic Health Record Sharing System (eHealth) and to share information on eHealth for relevant service needs

- Primary prevention: Health promotion, education and resource hub

- Secondary prevention: Health risk factors assessment and chronic disease screening

- Tertiary prevention: Chronic disease management and community rehabilitation

- Primary prevention services provided by the Core Team, including nursing, pharmacy and social work consultation service, and health promotion and activities are free of charge

- The Government provides subsidies to patients for medical consultation, medical laboratory tests, individualised allied health services and Chinese medicine acupuncture and acupressure treatment by network service providers in the community

- Co-payment for part of the service costs are required to strengthen the ownership of individuals’ own health management

Family Doctor for All

Family doctors, as the first point of contact for individuals and families in the healthcare process, are the main provider of primary care, which is the first level of care in the whole healthcare system. They provide comprehensive, continuing, whole-person, co-ordinated and preventive care to individuals and their families to ensure their physical, psychological and social well-being.

The Government has been promoting the “family doctor for all” concept since 2005 after the consultation document “Building a Healthy Tomorrow”, which emphasised on the provision of preventive care and continuity of care through family doctor and family doctor as patient’s first point of contact. More detailed proposals were put forward in the later consultation documents “Your Health, Your Life Consultation Document on Healthcare Reform” in 2008 and “Our Partner for Better Health - Primary Care Development in Hong Kong : Strategy Document” in 2010, including incentivising individuals to undertake preventive care through private family doctors, and developing a Primary Care Directory with appropriate training and qualification requirements for the register of family doctors so as to promote the family doctor concept and continuous enhancement of quality of primary care.

To curb the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), the Government has launched “Towards 2025: Strategy and Action Plan to Prevent and Control Non-communicable Diseases in Hong Kong” (SAP) in 2018. One of the initiatives in the SAP is to strengthen the health system at all levels, in particular comprehensive primary care for prevention, early detection and management of NCDs based on the family doctor model. A summary of the Government’s advocation of family doctor concept is at Table 2.4.

Going forward, the “Family Doctor for All” concept will remain as a fundamental guiding principle for the development of various primary healthcare policy under the Blueprint. The Government will require all family doctors and healthcare professionals participating in PHC service provision to be enlisted on the PCR and commit to using the RFs, including those enrolling in government-subsidised programmes such as the EHCV Scheme and CDCC Scheme, in order to provide quality assurance to users of PHC services, establish the “gold standard” for PHC service providers, and provide incentives for PHC professionals to adopt best practices and participate in co-ordinated care (see Recommendation 3.2). For the public, we will also propose registering with a family doctor as one of the pre-requisites for joining the CDCC and EHCV Scheme to cultivate a long-term family doctorpatient relationship between the patient and his/her family doctor in order to achieve the objectives of family-centric continuous and holistic primary care due to the sustained nature of chronic diseases (see Recommendation 2.2; 4.1 and 4.2). The ultimate goal is to have all members of the public to each be paired with a family doctor of their own, along with their family members, who would act as their personal health manager for development of personalised care plan with the support and assistance of DHCs.

Table 2.4

Family Doctor Concept Advocated by the Government

- Family doctor is the major primary care service provider who provides comprehensive, family-centric, continuing, preventive and co-ordinated care to you and your family members, taking care of the health of you and your family members.

- Apart from treating and caring of acute and chronic diseases, a family doctor also plays a crucial role in supporting you continuously in prevention and self-management of diseases.

- A family doctor has good understanding of your health conditions and needs. He can provide you the most suitable care and professional advice in promoting your health.

- Being your health partner, a family doctor provides comprehensive and continuing care to you and your family, including your children. Your family doctor knows your children well and can provide the most suitable preventive care as well as professional advice for any concerns on the health or development of your children.

- Being a health partner of you and your family, a family doctor provides continuing care and anticipates your changing needs during different stages of life.

- Growing old is one of the normal stages of life. Ageing brings about physical, psychological and cognitive changes or decline. Yet, some changes are not normal and may be early symptoms of underlying diseases. Should there be any suspicion of abnormal body changes, it is wise to seek advice from your family doctor who offers assessment and treatment tailored to your needs.

- Furthermore, a family doctor also helps you to prevent diseases by various means such as vaccination and evidence-based screening.

DHC’s Support to Family Doctors

As a hub with multiple access points, DHCs would support PHC family doctors by acting as care co-ordinators, accepting and making referrals to primary care providers in the community for consultation, co-ordinate, synergise and maximise community health services, as well as build and strengthen the social support to sustain the health initiative on the individual and community levels through medical-social collaboration. DHCs are set to complement but not compete with PHC doctors or similar service providers on first contact medical care. DHC are equipped with the necessary supportive healthcare services and are set to act as the district co-ordinators and resource hubs for territory-wide PHC services. On the other hand, pilot PHC initiatives could also be implemented via the district-based community health system to provide evidence-based results for the Government in planning long-term territory-wide PHC policies.

Through eHealth, DHCs would collect and analyse information related to the district’s population health for Government’s healthcare service planning, strategic purchasing, and monitoring and evaluating the performance of care providers (see Chapter 6). DHCs would also serve as a district health resource hub to collect information on healthcare resources available in the district. Such information can be used by the general public and facilitate individualised care where necessary.

DHCs are key channels on the community level which complement and deliver the Government’s healthcare policies and initiatives. For example, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the DHCs and DHC Expresses have been performing their frontline roles in different districts by actively taking part in anti-epidemic work on the district level. The epidemic prevention and control work carried out by DHCs on the district level includes providing COVID-19 vaccination service, distributing anti-epidemic supplies and rapid testing kits, disseminating COVID-19-related health information, organising anti-epidemic education activities, providing hotline support service to the public, and providing rehabilitation support for COVID-19 recoverees, etc. These functions are essential in contributing to the Government’s preparedness and response during the epidemic as they provide accessible and efficient information and resource dissemination on the district level.

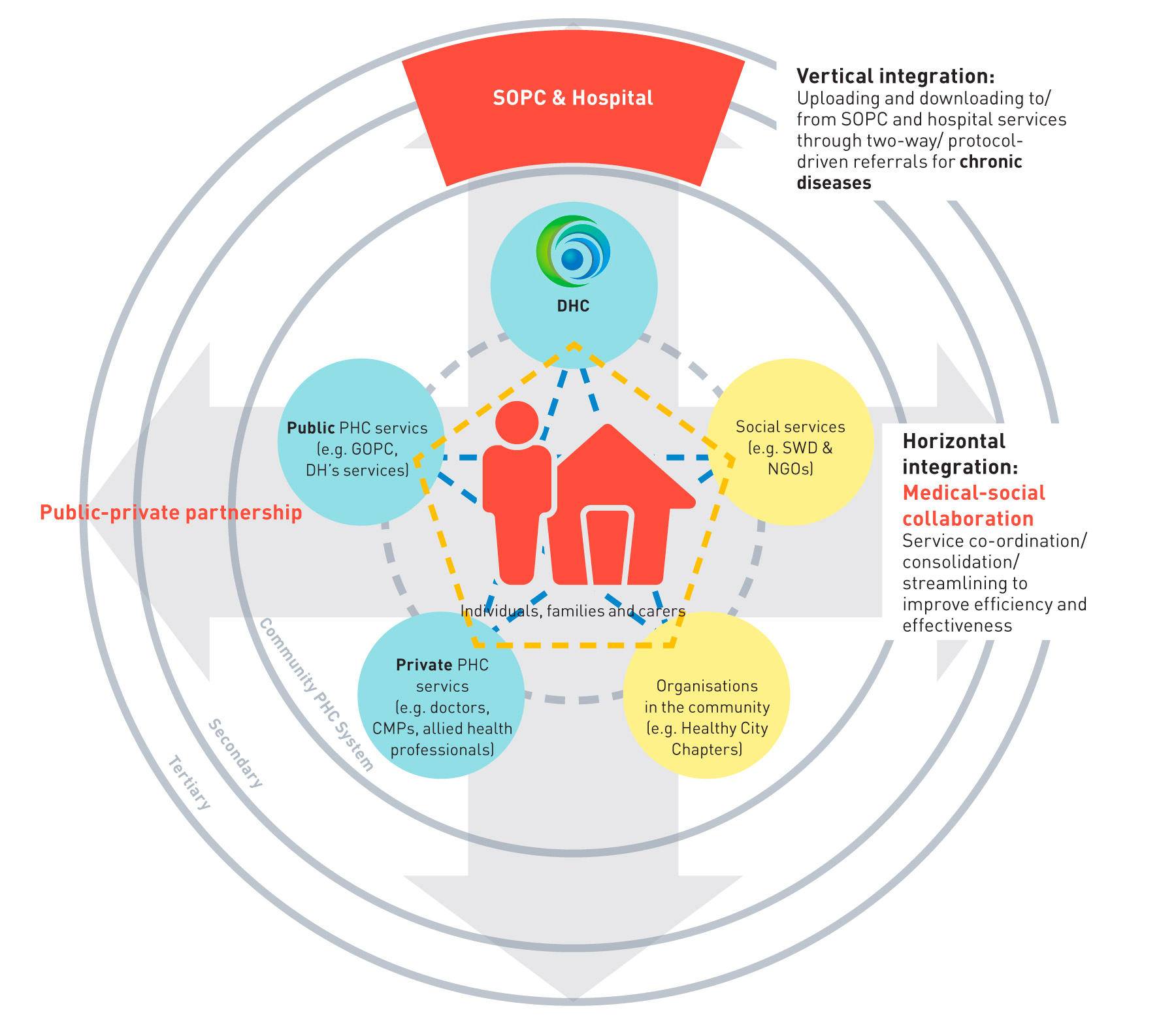

Riding on the above development, we propose to further develop a district-based family-centric community health system based on the DHC model with an emphasis on horizontal integration of district-based PHC services through service coordination, public-private partnership and medicalsocial collaboration, as well as vertical integration or interfacing with secondary and tertiary care services through protocol-driven care pathway for specified chronic diseases supported by welltrained primary care medical practitioners playing the role as family doctors in order to further strengthen the concept of “Family Doctor for All” especially in matters concerning chronic disease management (see also Recommendation 2.2 and Chapter 3).

The PHC sector is envisaged to be integrated and co-ordinated to serve as a gate-keeper to the public secondary healthcare system. It aims to improve service efficiency and effectiveness, as well as helping patients navigate each level of the healthcare system efficiently. A conceptual model of the district-based community health system is in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1:

Vertical and horizontal integration of healthcare services in a district-based community health system

Consolidation of Public Primary Healthcare Services

As discussed above, there appears to be service and resource overlap within the public healthcare sector. Also, there is room for various PHC services to be consolidated. As the service model and scale of DHC continue to grow and solidify, we see the need to drive the consolidation of public PHC in DH and HA in order to reduce service duplication and enhance resource efficiencies.

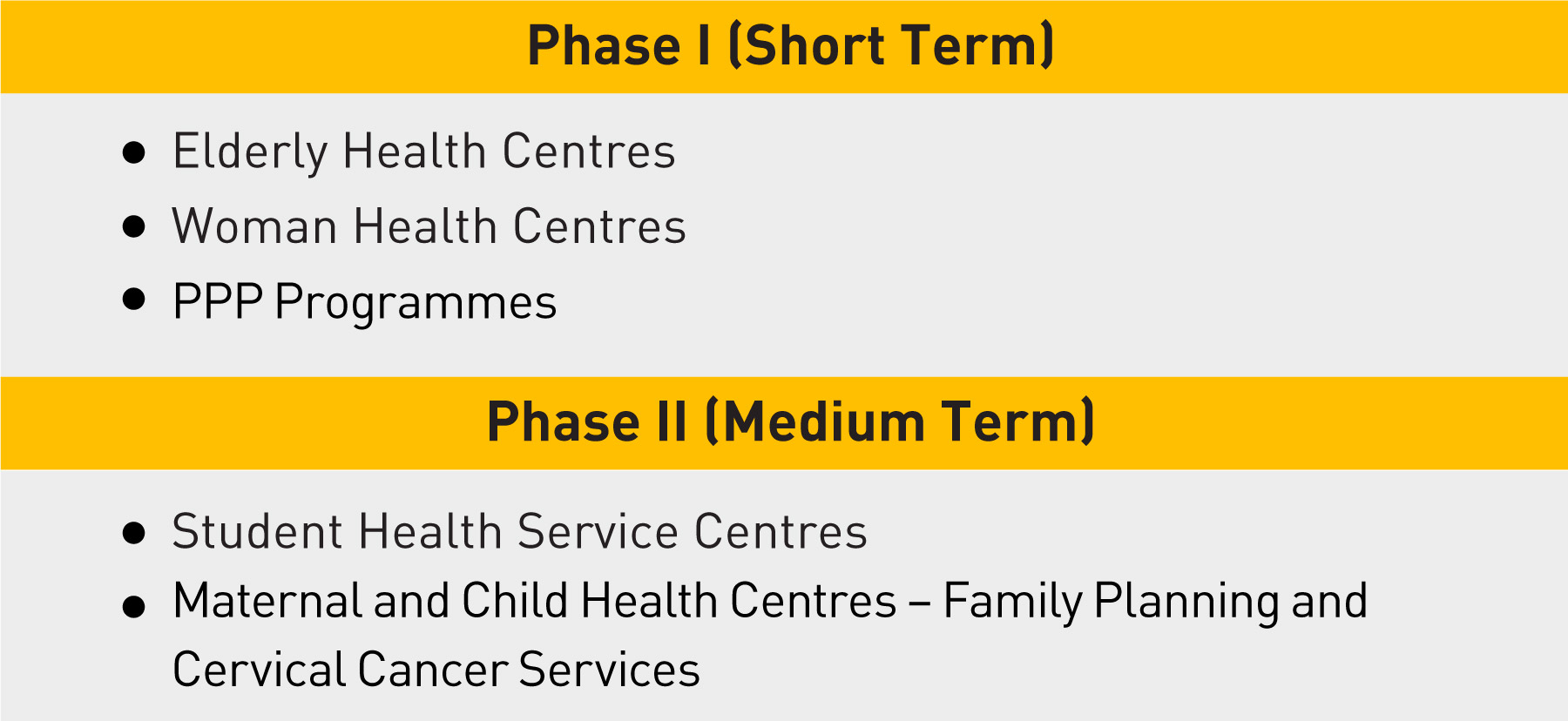

Among a wide range of clinical services provided by DH, while most of them carry significant public health functions, a few of them share similar PHC objectives. As the district-based community health system evolves, the Government proposes to progressively migrate PHC services under DH to the district-based community health system, especially those with room for more efficient delivery on the district level through an alternative approach, with a view to facilitating provision of integrated PHC services within the district-based community health system and reducing service duplication. Taking into account the level of synergy and impact of service transition, a phase by phase approach is recommended as highlighted in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5

Migration of direct services from DH

Elderly Health Centres

Since 1998, DH has established 18 EHCs in each of the districts to address the multiple health needs of the elderly by providing to them integrated PHC services. Enrolled members aged 65 and over are provided with various healthcare services, including health assessment, counselling, health education and curative treatment, delivered by a multidisciplinary team. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, EHCs disseminated COVID-19-related health information, provided talks as well as offered COVID-19 vaccination service to elderly. They also participated in distribution of anti-epidemic supplies and rapid testing kits. With the increase of an ageing population, EHCs face the challenge of limited service quota to a large unmet demand.

To achieve service synergy, we have devised a collaboration model for the EHC and DHC within the same district with the first DHC in Kwai Tsing, which commenced operation in September 2019, as a start. The EHCs have been actively collaborating with DHCs to implement joint protocols for crossreferral of clients.

As EHC and DHC services become increasingly complementary to each other, we shall begin to migrate EHC services to DHCs with a step by step approach. Upon migration, EHC members shall continue to receive health assessments and health education at DHCs with a stepped up protocol catering for the elderly. Meanwhile, medical needs arising from their chronic and elderly conditions shall be cared for at GOPCs.

Woman Health Centres

Currently, DH’s three WHCs provide PHC services to women and empower women to make the life choices that are conducive to their health. Women may seek appropriate healthcare and/or social services at the centres when necessary. They provide accurate and updated information on women’s health issues as well as the access to relevant community resources.

In 2021, the Breast Cancer Screening Pilot Programme was rolled out to provide breast cancer screening for eligible women. Under the programme, WHC members will receive mammography screening at a subsidised rate upon indication.

Similar to the EHC, WHC and DHC services are increasingly complementary to each other. With the conclusion of the Breast Cancer Screening Pilot Programme, we shall commence to migrate WHC services to DHCs and also private healthcare providers through PPP as appropriate. After service migration, stepped up health assessment tools will be used by DHCs to cater for specific women’s health needs. DHCs shall assume the role of provision of health assessment, education and individual counselling for women.

In the longer term, the Government will recommend alternative approaches on healthcare service delivery at those direct PHC service centres. The aim is to allow for more cost-effective provision of healthcare services on top of current service delivery model within the district-based community health system and at the same time maximise overall population health beyond the existing direct service delivery mode (see Chapter 3 and 4).

Primary healthcare functions of Hospital Authority

HA Patient Programmes, covering HA patients, aim to achieve the Government’s objective of building an integrated healthcare system with respect to HA services. While its focus is mainly on secondary and tertiary care, it has also implemented a number of PHC-related services (including some strategic purchasing programmes). Alongside the evolvement of the district-based community health system, subject to the HHB’s policy consideration and Primary Healthcare Commission’s oversight, these programmes could be expanded, discontinued or modified to suit the latest policy / programme objectives. For example, patient empowerment, community support, maintenance rehabilitation and nursing services in primary care currently provided by HA are considered suitable for collaboration with DHCs. The Government will continue to work with HA on the integration of different services to provide comprehensive patient care, to optimally allocate resources and to avoid duplication.

One of the most important PHC functions of HA rests with its GOPCs. Whilst HA will continue to oversee the GOPCs as part and parcel of a complete patient journey and for the performance of a safety net and public health function, the proposed positioning of GOPCs in the management of chronic diseases will be further discussed in Recommendation 2.3. The establishment of the primary-secondary healthcare pathway, in particular for targeted chronic diseases, will be discussed in Chapter 3 - Recommendations 3.2 and 3.3.

As regards CM services, HA has also been actively promoting the collaboration between the CMCTRs and DHCs. For example, during the “San Jiu Tian” Period in December 2021, CMCTRs collaborated with three DHCs/DHC Express (including Kwai Tsing DHC, Sham Shui Po DHC and Sai Kung DHC Express) to provide Tian Jiu services on a trial basis and organise CM thematic seminars, which were well received by the members of the public. To fully unleash the potential of CM in PHC settings and further promote the development of CM in Hong Kong, the Government will continue to enhance PHC services provided by the CMCTRs through service planning, explore the positioning of CMCTRs within the PHC system, and further the collaboration between CMCTRs and other PHC stakeholders.

Medical-social collaboration

To enable the concept of whole-person care, we need to strengthen the medical-social collaboration aspect in the district-based community health system. The social service sector plays an important role in the district-based community health system by providing an effective and complementary social support network. The district-based community health system should therefore support the collaboration between healthcare and social services. While patients receive medical care in their districts, enhancing the capacity of patients’ carers and family is also necessary. They help to manage patients’ health (including both physical and mental), make appropriate healthcare decisions and respond to emergencies.

Upon the establishment of the district-based community health system, co-operation between the community support provided by DECCs/ NECs and healthcare support provided by public PHC services will be enhanced. This will facilitate medical-social collaboration, family-centric and coordinated care, particularly to hidden and vulnerable elderly persons and their carers.

Recommendation 2.2

Enhance chronic disease management through the private primary healthcare sector

As discussed in Chapter 1, to achieve healthcare system sustainability, a shift in the emphasis of the present healthcare system to a preventionoriented healthcare model with a focus on chronic disease management is important. Due to its prevalence, burden and costliness, intervening chronic diseases at an early stage is important. Through the district-based community health system, the Government aims to incentivise citizens to prevent the development of chronic diseases. The Government also hopes to facilitate early identification and provide timely intervention of designated chronic diseases at the community level with the assistance of healthcare service providers in their localities. For those individuals diagnosed with chronic diseases, we strive to prevent and manage associated complications to reduce need for hospitalisation.

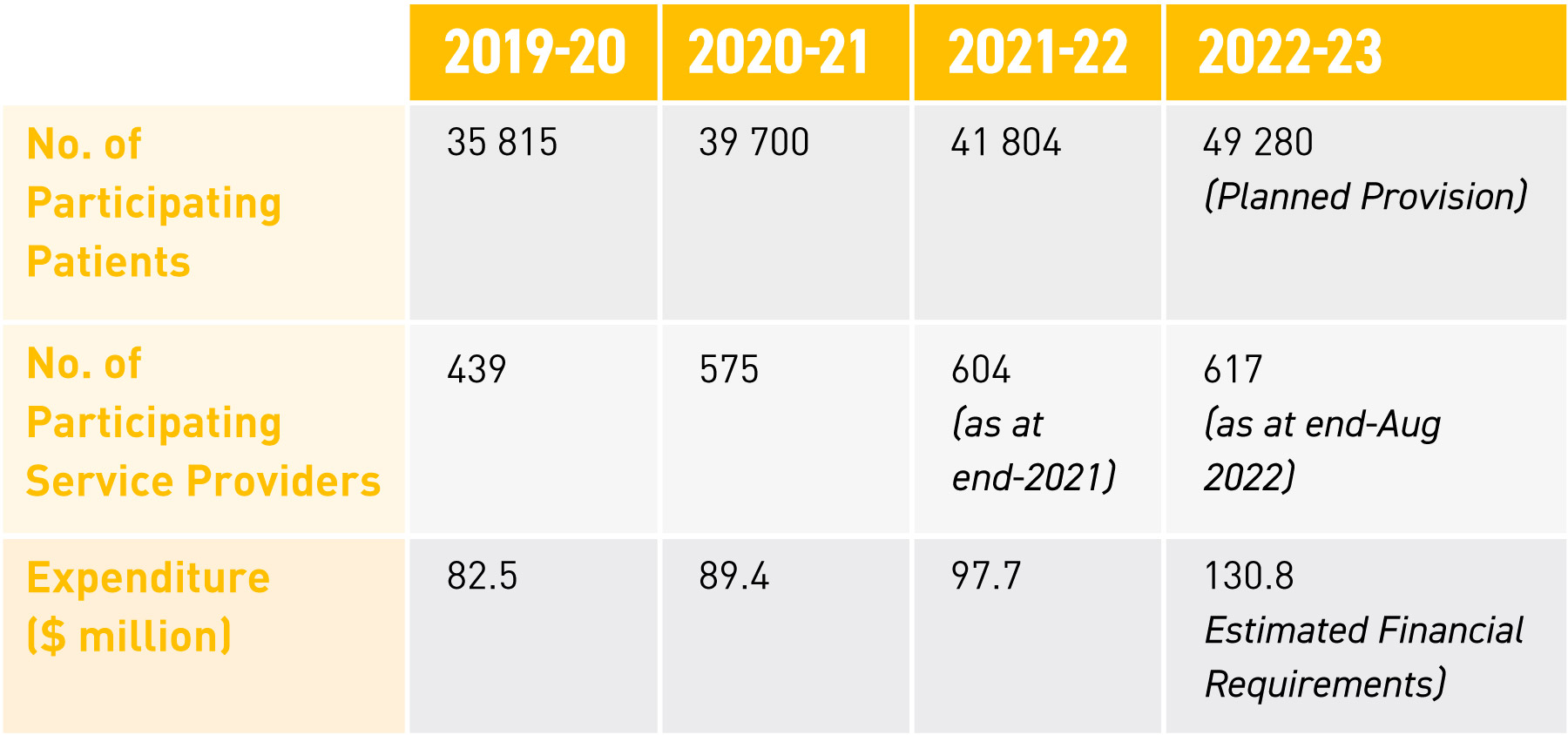

As discussed in paragraph 36, the GOPC PPP was launched in 2014 in phases with an aim to help relieve the demand for HA's general out-patient services by leveraging on the resources of the private sector. Under the GOPC PPP, clinically stable patients with HT and/or DM originally being taken care of by GOPCs would be invited for voluntary participation in the Programme and opt for care from a private doctor of their choice to follow up on their chronic diseases. In addition to relieving the pressure off the public healthcare system, the Programme also aims to cultivate a long-term doctor-patient relationship between the patient and his/her family doctor in order to achieve the objectives of continuous and holistic primary care. To date, over 600 private medical practitioners have participated in the GOPC PPP Programme, covering all 18 districts of Hong Kong. Service provisions, participating service providers and expenditure of GOPC PPP over the years are listed in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6

Service statistics of GOPC PPP

Riding on the existing GOPC PPP, HA has introduced the Co-care Service Model in late 2021 by gradually extending the patient invitation pool to patients of HA SOPCs. In consultation with HA’s clinical expertise, the Co-care Service Model is being piloted in three specialties viz. Medicine (MED), Orthopaedics & Traumatology (O&T) and Psychiatry (PSY). Eligible patients who had been following up at MED, O&T and PSY SOPCs were invited by batches to participate in the programme under the Co-care Service Model.

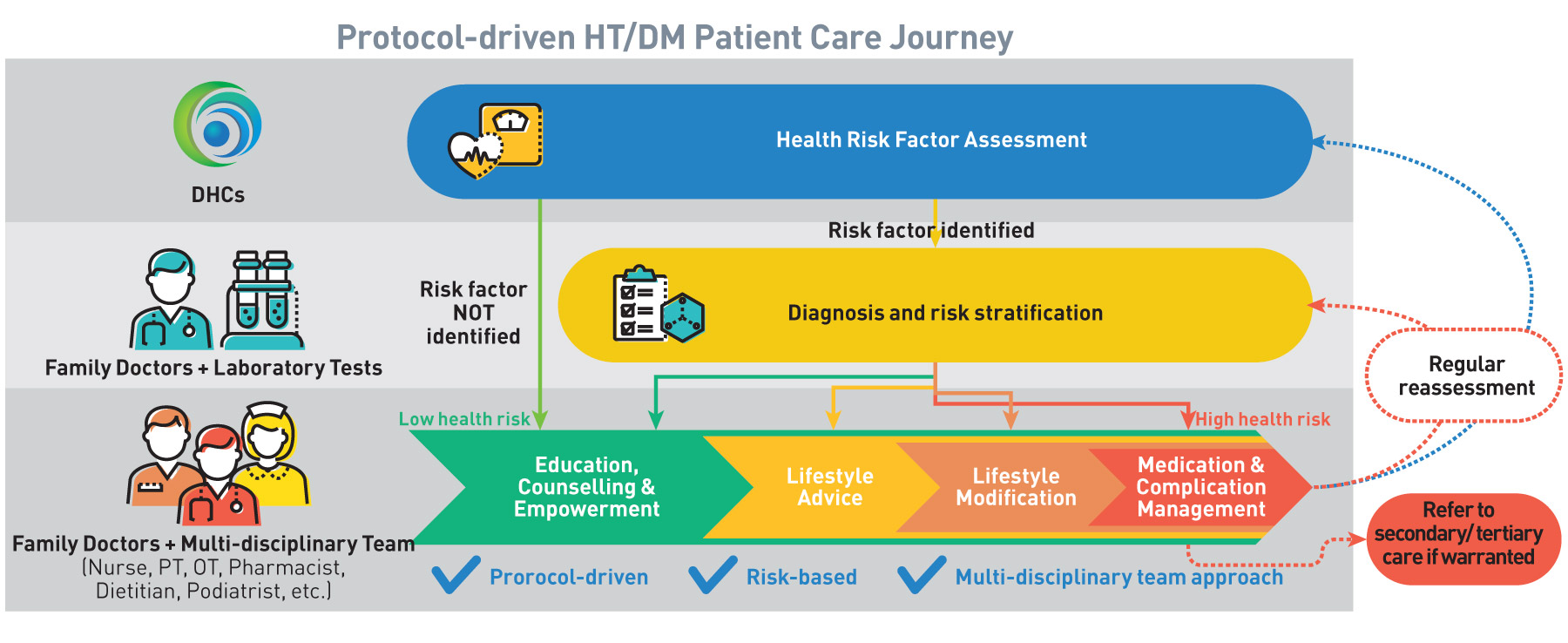

On the other hand, as one of the existing DHC services, DHCs would proactively identify people with high risk of HT and DM through basic health risk factor assessments for further diagnosis by network medical practitioners from the private sector. Those with confirmed diagnosis would be invited to join the DHCs’ protocol-driven structured HT/DM management programmes. Under the DHC HT/DM management programmes, these cases would be managed by a primary care doctorled multi-disciplinary team consisting of nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals, social workers and other workers in healthcare and social services under the care co-ordination of DHC. Subsidised individual allied health services are offered under the DHC HT/DM management programmes.

The existing DHC chronic disease management protocol has been developed with reference to the relevant Reference Frameworks (RFs) in primary care settings issued by the Government and the Risk Assessment and Management Programme (RAMP) introduced in HA for HT and DM patients, which includes complication screening, interventions and education from a multi-disciplinary healthcare team, proven to be cost-effective. To further incentivise DHC members to receive holistic care in the community, we proposed in the 2020 Policy Address to implement a Pilot Programme for chronic disease management by providing subsidised medical consultation by private medical practitioners for DHC members who are newly diagnosed with HT or DM, in addition to the prevailing screening and allied health services which are already subsidised for DHCs members.

Figure 2.2:

Protocol-driven HT/DM Patient Care Journey

We propose to introduce a “Chronic Disease Co-Care Scheme” (CDCC Scheme) to provide targeted subsidy for the public to conduct diagnosis and management of target chronic diseases (especially HT and DM) in the private healthcare sector through “family doctor for all” and a multidisciplinary public-private partnership model. Through the CDCC Scheme, we hope to facilitate early identification and timely intervention of chronic diseases so as to reduce the demand for specialised and hospital services. It also provides an additional choice of services for chronic disease patients outside of the public healthcare system. While chronic diseases are considered as an appropriate disease-based intervention point for the CDCC Scheme due to their high prevalence, treatment efficiency and financial burden if otherwise left untreated, the introduction of the CDCC Scheme is also expected to cultivate a longterm family doctor-patient relationship between the patient and his/her family doctor in order to achieve the objectives of family-centric continuous and holistic primary care due to the sustained nature of chronic diseases.

Based on a co-payment system, chronic disease patients with higher affordability are envisaged to obtain the required PHC services through the network of participating PHC professionals of the CDCC Scheme of their choice. Service providers for the management model are subject to the Government’s monitoring and quality assurance, and shall follow the standardised care protocol and referral mechanism for management of chronic diseases (See Chapter 3 - Recommendation 3.2 and 3.3).

As announced in the 2022 Policy Address, the CDCC Scheme shall be implemented in a three-year pilot basis with a view to testing out the model. The Government shall invest into the CDCC Scheme in order to encourage all citizens to benefit from early intervention and management of these targeted chronic diseases. The enhancement of PPP in the primary care setting would contribute to the quality and efficiency of publicly-funded primary care services and alleviate pressure on the public healthcare system. The subsidisation model will be discussed at Chapter 4 - Recommendation 4.1.

Recommendation 2.3

Review the position of the public general outpatient services

The current public healthcare system serves as an essential safety net for the population, especially those who lack the means to pay for their own healthcare. We need to maintain and improve the coverage and quality of healthcare services provided for those who cannot afford private healthcare services so that no one should be denied adequate healthcare due to lack of means.

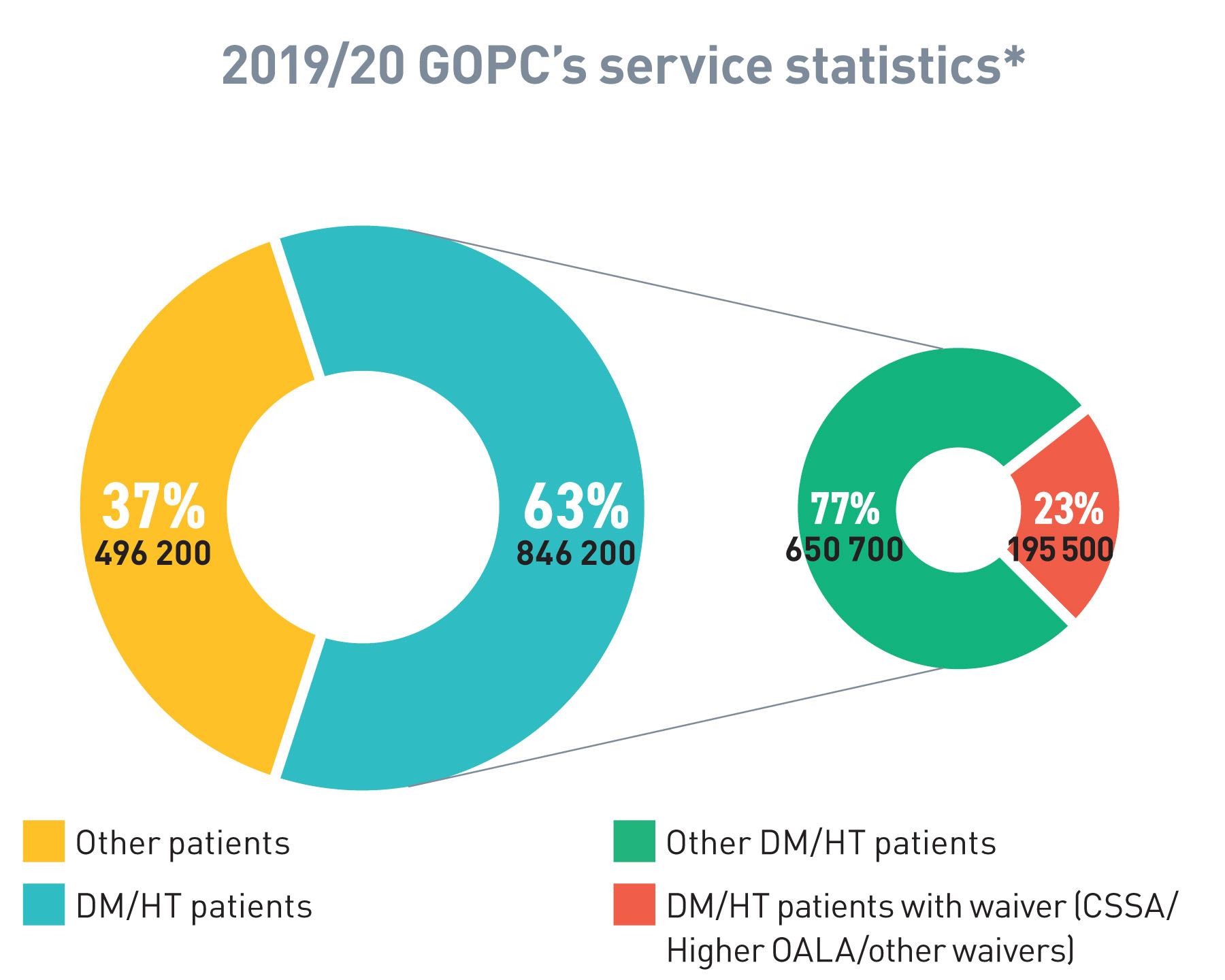

HA has been offering PHC services through 73 GOPCs (including three Community Health Centres (CHCs)) with major service users being the elderly, the low-income group and the chronically ill. Patients under the care of GOPCs can be broadly divided into two main categories, namely chronic disease patients with stable conditions (e.g. DM and HT) and episodic disease patients with relatively mild symptoms (e.g. influenza, colds). In 2019/20, excluding GOPC patients with civil service or HA staff benefits, 63% of GOPCs’ patients were DM/HT patients (846 200 patients), among which 23% (195 500 patients) were recipients of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance, Higher Old Age Living Allowance or other fee waivers. The remaining 37%

were non-DM/HT patients (see Figure 2.3).

GOPCs also assume a major role in the community during COVID-19. Since July 2020, GOPCs have been supporting the Government in distributing specimen collection packs and collecting specimens, and vending machines were installed at selected GOPCs to assist individuals in need to obtain specimen collection packs. HA has also been providing COVID-19 vaccination services to the general public through different channels (including provision of vaccination services at selected GOPCs since February 2021). During the fifth wave, HA had activated a maximum of 23 GOPCs into designated clinics for COVID 19 confirmed cases to help provide treatment and prescribe COVID-19 oral drugs for confirmed patients in the community presenting with relatively mild symptoms of infection, especially high risk patients. Starting from July 2022, HA also provides tele-consultation service through designated clinics to facilitate suitable COVID-19 patients to receive medical consultation and medication delivery service in the community. The designated clinics and tele-consultation service provided timely and appropriate medical support to patients at the community level.

The above illustrates the importance of GOPCs as a publicly-run PHC facility at the community level. Nonetheless, as discussed in paragraph 66, whilst the GOPCs would continue to be provided by HA as part and parcel of a complete patient journey for the performance of safety net and public health function, with the introduction of the above CDCC Scheme which aims to better utilise private PHC resources, we see the need to reposition GOPCs to enable targeted use of public resources. To ensure that the public healthcare system would continue to serve as an essential safety net for the population, it is proposed that GOPC service should take priority care of the socially disadvantaged population groups (especially low-income families and the poor elderly). In 2019/20, among GOPCs’ HT/DM patients (excluding patients with civil service or HA staff benefits), about 23% were fee-waiving patients (i.e. either recipients of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance or Higher Old Age Living Allowance or other fee waivers. As for chronic disease patients not among the above target group, which account for about 77% of the current GOPC chronic disease patients with DM and/or HT (excluding patients with civil service or HA staff benefits), instead of using public PHC services, they may also choose to seek private PHC services and join the CDCC Scheme for chronic disease care.

Figure 2.3:

Target users of GOPC’s service

*The above figures exclude service users with civil service benefit/HA benefit

Through an appropriate referral mechanism, it is envisaged that some of the chronic disease patients currently under GOPCs’ care could be diverted to the private healthcare sector through the abovementioned CDCC Scheme. The freed up resources could allow GOPCs to provide better care for their target chronic disease patients through wider utilisation of RAMP. The protocol-driven referrals will be further discussed in Chapter 3 - Recommendation 3.3.

With the territory-wide rollout of the CDCC Scheme and the repositioning of GOPCs, the existing GOPC PPP and Co-care Service Model will be reviewed with a view to streamlining service focus to ensure the cost-effective use of public funds and to explore the feasibility of introducing other PPP programmes for strategic purchasing of PHC services from the private sector (see Chapter 4).

Chapter 2- DEVELOP A COMMUNITY-BASED PRIMARY HEALTHCARE SYSTEM: Action Plan

2.1 DHCs

To setup 7 DHCs and 11 DHC Expresses

Action: Short

To set up 18 DHCs across the territory

Action: Medium - Long

To review the DHC service model

Action: Short - Medium - Long

2.1 Migration of PHC Services

To migrate public PHC services from DH

Action: Short - Medium

To migrate PHC services (e.g. patient empowerment, community support, etc.) from HA

Action: Short

To enhance collaboration between DHC and DECCs/NECs

Action: Short

2.2 “Chronic Disease Co-Care Scheme” (CDCC Scheme)

To review the Sham Shui Po DHC Pilot Programme for chronic disease management upon completion of pilot programme

Action: Short

Upon review of the Pilot Scheme, to gradually expand the CDCC Scheme to all HT and DM patients in Hong Kong

Action: Short - Medium - Long

To review the CDCC Scheme and explore possible expansion

Action: Short - Medium - Long

2.3 Review of-GOPCs’ positioning

To divert GOPCs’ non-target group patients with HT and/or DM to receive subsidised treatment provided by private sector via CDCC Scheme

Action: Short - Medium - Long