Consolidate primary healthcare resources

Public healthcare resources should be allocated to cater to the healthcare needs for all in a sustainable manner. As illustrated above, there will be a need to increase public expenditure on primary healthcare (PHC) services as an investment so as to achieve the target of reallocation of public health resources to achieve a sustainable health system. A focus on chronic disease prevention and management is widely established as one of the most cost-effective ways to envisage sustainability of the healthcare system. With the investment, it is expected that there will be an increase in the overall health expenditure in PHC from both the public and private sectors. The additional resources required would have to be drawn either through reallocation from existing resources or injection of new ones.

To improve accessibility to quality PHC for the general public and redress the imbalance between the public and private healthcare sectors, strategically the Government strives to optimise the utilisation of private healthcare resources and leverage on the private sector’s capacity for providing PHC services, with a view to relieving pressure on the public sector and thereby enhancing the sustainability of the healthcare system. As recommended in the “Your Health Your Life” Healthcare Reform Consultation Document in 2008, to pursue PPP in healthcare in Hong Kong to subsidise the community to make better use of resources in the private sector for delivering service for public sector patients, thus allowing the public healthcare system to continue to serve as an essential safety net for the population and be accessible to those who lack the means to pay, we have recommended that PHC services should be purchased from the private sector and patients should be partially subsidised to undertake preventive care in the private sector [19]. In this connection, the Government proposes to improve the existing financing schemes, with various forms of subsidisation and PPP through strategic purchasing, to enhance the accessibility and affordability of PHC services in the community.

Public Health Expenditure

Over the years, the Government has made substantial and sustained investment to improve our PHC services. We have progressively achieved a substantial increase in recurrent health expenditure to almost $127.8 billion in the 2022-23 Estimates, amounting to 22.7% of total government recurrent expenditure. Nonetheless, according to the Domestic Health Accounts (DHA), around 83% of public health expenditure was spent on secondary and tertiary healthcare whereas only 17% was put on PHC in 2019/20 (See also Chapter 1) [7].

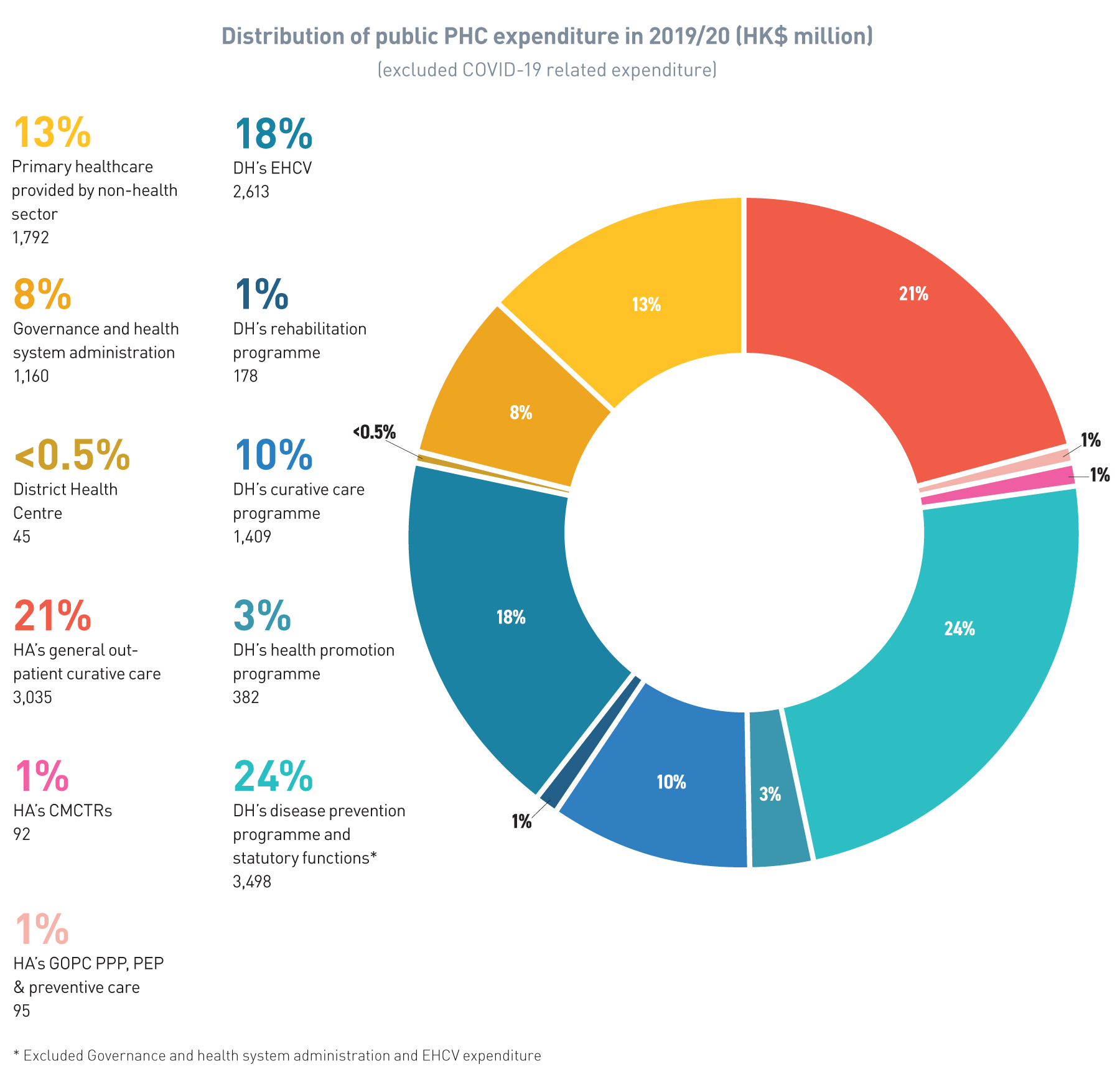

As elaborated at Chapter 2, the Government has been developing the public PHC system through strengthening the services of DH and HA, and subsidising NGOs in providing PHC services and launching public education. In recent years, the Government has launched various PPP programmes as recommended by previous consultation documents with a view to tapping into the private healthcare sector resources in meeting public PHC service demand. To enhance public awareness in disease prevention and self-health management, offering greater support for patients with chronic diseases, and relieving the pressure on specialist and hospital services, the Government has also launched the DHC scheme to enhance district-based PHC services throughout the territory progressively. The distribution of public PHC expenditure in 2019/20 (excluding COVID-19 related expenditure) is illustrated at Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1:

The distribution of PHC expenditure in Public Health Expenditure

Source: DHA[7]

Private Health Expenditure

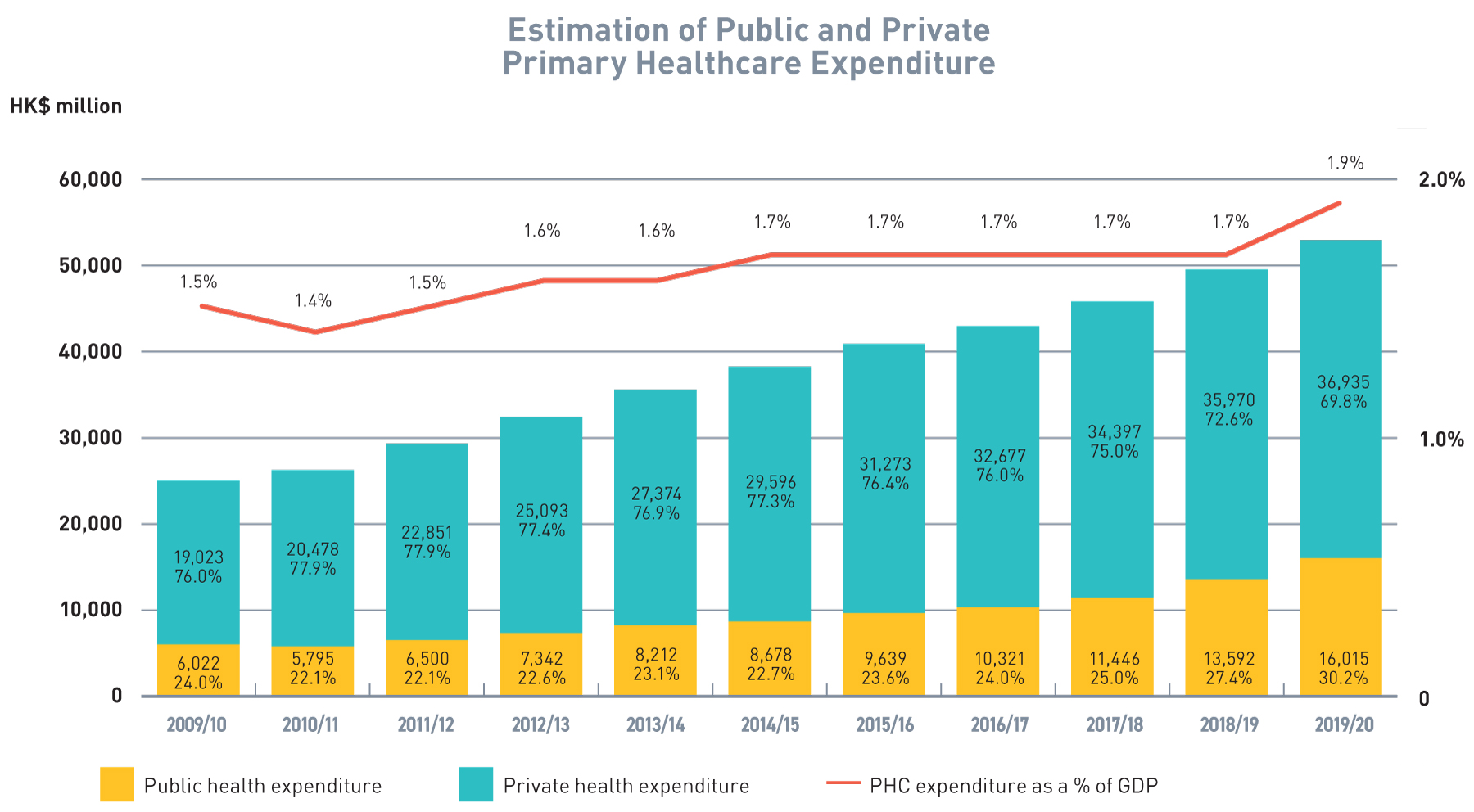

The private sector is the major provider of PHC services. As aforementioned in Chapter 1, public health expenditure and private health expenditure have been increasing in parallel. From 1989/90 to 2019/20, the total health expenditure has increased by 410% cumulatively in real terms. In 2019/20, the total health expenditure amounted to $188,709 million (6.7% of GDP) and per capita spending was $25,135, in which the overall PHC expenditure was $52,950 million, accounting for only 29.4% of current health expenditure. Private PHC expenditure6 made up around 69.8% of PHC expenditure in 2019/20 (Figure 4.2) [7].

6 While the Government does not have full grasp of the total private health expenditure on PHC in the market due to difficulty in differentiating PHC from other secondary out-patient services in the private sector, we have taken the assumption that 50% of out-patient curative care and 50% of administration of health financing are classified as PHC services in the private sector.

Figure 4.2:

Estimated PHC expenditure in the public and private sectors (in HK$ million) and the proportion of PHC expenditure as a % of GDP

Source: DHA

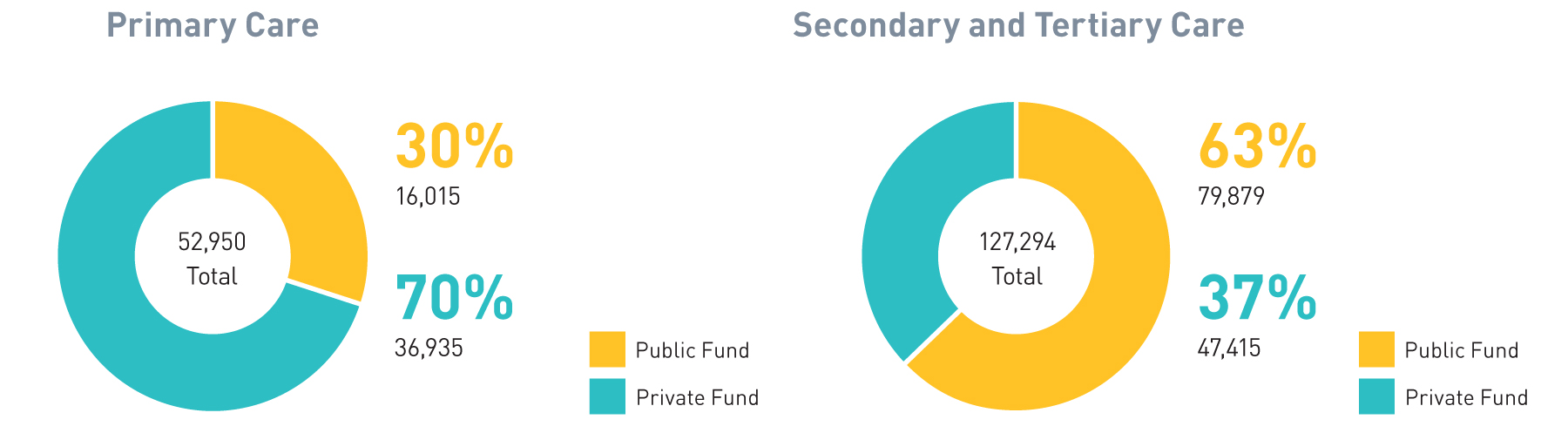

The situation is different for secondary and tertiary care where the public sector is the major provider of services with private expenditure accounting for only 37% (Figure 4.3) or $47,415 million. Given the limited supply of services in private secondary and tertiary care, there would be limited scope for the Government to achieve savings in secondary and tertiary care, which are curative in nature, through PPP.

Figure 4.3:

Composition of Current Health Expenditure (in HK$ million), 2019/20

Source: DHA

As illustrated in Chapter 1, Hong Kong is facing a key and long-standing challenge on significant public-private imbalance in the entire healthcare system. While private services offer more choices and flexibility to patients, they all come with a price. Private healthcare services, which are paid mostly out-of-pocket7, are more expensive than those in the public sector, and could be extraordinarily costly when more complicated and complex inpatient services are involved, and hence are not affordable to the majority of the general public.

On the other hand, the high quality and heavily subsidised public healthcare services have resulted in an ever-growing demand for public healthcare services, overstretching the public system as well as lengthening waiting time for services. In 2021, 87.2% of doctor consultations for chronic disease management were in the public sector, and there was an increasing trend of reliance on public services along with ageing of the population.

7 In 2019/20, 65.2% of private health expenditure and 77.1% of private health expenditure on PHC was paid by out-of-pocket payment, as mentioned in Chapter 1.

Public-private partnership

The sustainability of public healthcare services is at stake, and a better balance between the public and private sectors through Public-private partnership (PPP) is critical. Pursuance of PPP through a common platform between the public and private healthcare sectors involving medical specialists, general practitioners (GPs) and other disciplines of healthcare professionals would help address the current significant imbalance between the public and private sectors. Under PPP, patients are offered more choices and better means for private services, and the over-reliance on the public sector would be reduced. It also comes with other added benefits such as facilitating integrated medical care in a comprehensive, personalised and holistic manner; promoting healthy competition and collaboration between the public and private sectors; benchmarking service efficiency and effectiveness, and facilitating cross-fertilisation of expertise and experiences among medical professionals etc.

Over the years, the Government has rolled out different initiatives aiming to tap into resources of the private sector to enhance PHC development. Some examples of PPP, including DHC and GOPC PPP, have been discussed in Chapter 2. In addition, DH has also implemented various PPP initiatives, such as the Elderly Health Care Voucher (EHCV) Scheme, Vaccination Subsidy Scheme (VSS), and Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme (See Table 4.1).

These programmes have helped address service gaps and relieve pressure on the public sector. For the private sector, on top of business considerations, PPP programmes have provided connection, collaboration and cross-fertilisation of expertise with the public sector. For patients, these programmes have offered greater choices, shorter waiting time, better environment, personalised care and convenience at the same or lower fee, affordable co-payment, and in certain cases, they enjoy continuity of care under a family medicine concept. All these have assured that PPP is the right direction for further development based on the solid foundation established throughout the decade.

Table 4.1

Key Examples of Public-private Partnership Schemes in Primary Healthcare

Department of Health

Health Bureau

Hospital Authority

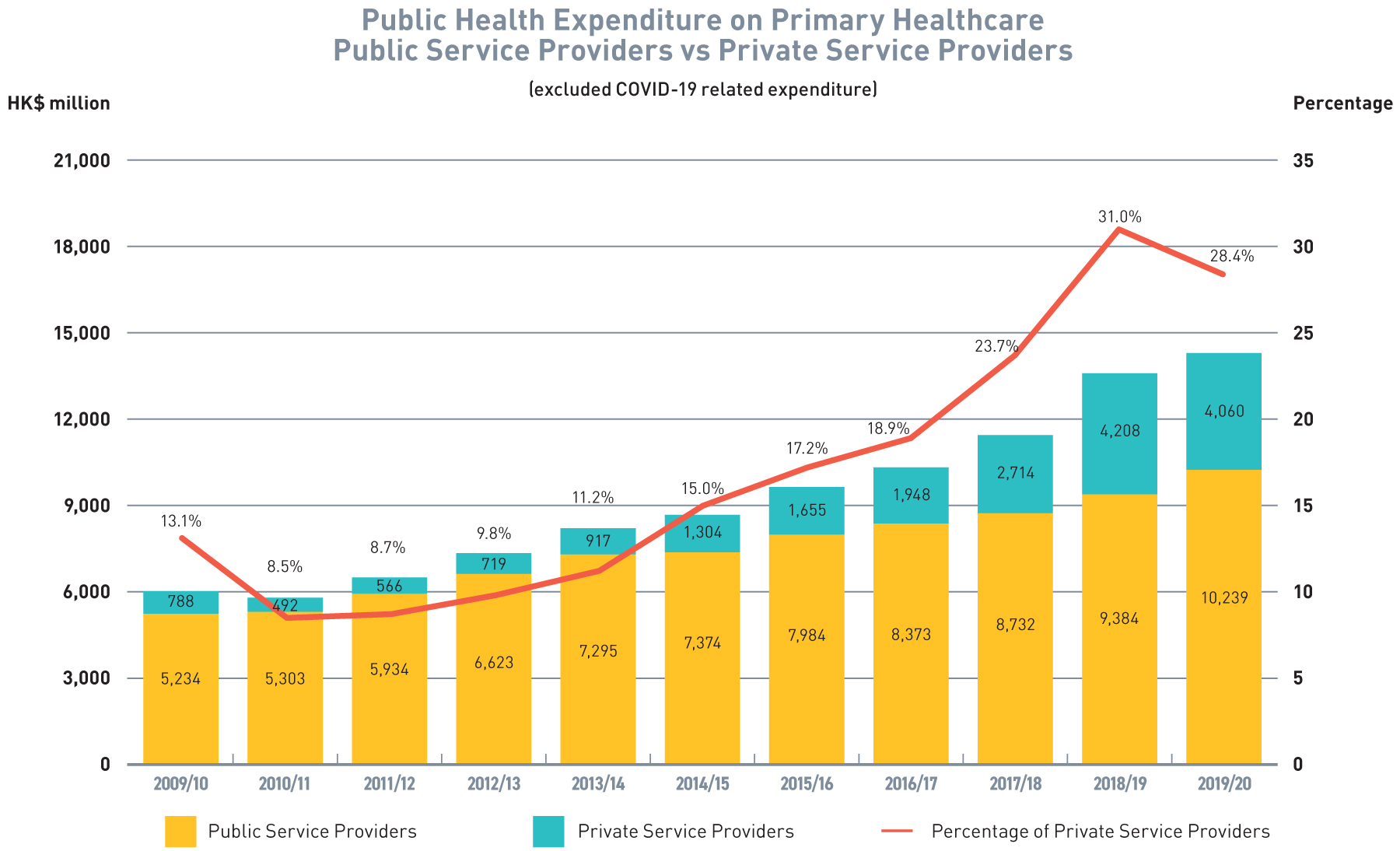

There is an increasing participation of private service providers in public PHC (Figure 4.4) that among the public expenditure on PHC, the share paid to private service providers has been increasing steadily over the past decade from only 8% in 2010/11 to about 28% (excluding COVID-19 related expenditure) in 2019/20.

Figure 4.4 :

Public health expenditure on PHC by public service providers and private service providers

Source: DHA

The Challenges

In order to shift the focus of the current health system towards PHC, there will be a need to expand expenditure on PHC services as an upfront investment so as to enable reallocation of healthcare resources from secondary/tertiary to PHC level and to attain better health outcome and sustainable healthcare financing and delivery model. Apart from injecting new resources through increasing public expenditure, we need to explore reallocation from and better utilisation of existing resources. Given the limited supply of services in private secondary and tertiary care, there would be limited scope for the Government to achieve savings in secondary and tertiary care, which are curative in nature, through PPP. The situation also leaves little room for the Government to relocate its resources on secondary/tertiary curative care into PHC notwithstanding its importance. In addition, the savings, or a reduced rate of increase in healthcare expenditure, with an investment in PHC, may only be realised in later years, as a result of deferring and reducing individual demand for secondary and tertiary care amongst an ageing population.

In considering utilisation of existing resources, one of the options is to rechannel the resources and improve existing PHC PPP or subsidised programmes in order to create synergy and direct private expenditure currently spent on PHC services (including individual direct expenses, medical benefits provided by employers or personal health insurance) to services that suits the concept of primary healthcare through relevant programmes supported by public resources under co-payment principle. We acknowledge that the existing programmes were launched at different times and are implemented on a programme basis without strategic assessment of the overall service demand-supply gap. Moreover, these programmes are planned, implemented, monitored, managed and financed respectively by DH and HA, and hence synergies among the programmes have been limited. In addition, the nature of those PPP programmes, especially those more popular ones, are mainly those involving one-off subsidisation without cultivating ongoing patient-doctor relationship or fulfilling the co-payment principle.

Our Aim

To unleash more potential benefits of PPP in providing PHC services, strategic purchasing, a tool to complement the existing dual-track healthcare system through co-ordinating and integrating the purchase and administration of PPP initiatives in a strategic and holistic manner, should be put in place to drive changes towards a more optimal healthcare system. In this connection, the Government aims to improve the existing financing schemes, with various forms of subsidisation and PPP through co-payment principle, to enhance the accessibility and affordability of PHC services in the community, and to channel resources more effectively towards quality, co-ordinated and continuous PHC with an emphasis on family-centric and prevention-oriented services, reduce service duplications, gaps, inefficiencies and mismatches between the public and private sectors PHC services, and ultimately bring about optimised, co-ordinated and integrated care to individuals and families to maximise their health benefits and outcomes.

The Government strives to strategically optimise the resources of the private health sector to make wider use of market capacity by adopting the co-payment principle to implement PPP PHC services. Meanwhile, the Government will reposition public PHC services to serve the underprivileged groups. This will encourage citizens with higher affordability to use private PHC services subsidised by the Government, and at the same time allow public PHC services to focus resources on the underprivileged groups. Indeed, the objective of PPP programmes is not meant to outsource public services to the private sector, but to provide a choice for citizens who can afford the relevant co-payment and foster public-private collaboration, thereby optimising the use of resources in the healthcare system and enabling better patient care and outcomes.

Overall, it is estimated that the implementation of various recommendations of the whole Blueprint for shifting the healthcare system towards prevention-oriented, family-centric PHC system will improve both the efficiency and financial sustainability of the healthcare system as a whole, as well as reduce the avoidable demand for the much more costly secondary and tertiary healthcare so as to achieve the optimal balance between primary and secondary/tertiary healthcare in total health expenditure. For instance, the proportion of primary and secondary/tertiary healthcare may progressively increase from 3:7 to 3.5:6.5, or even 4:6 in the long term with a view to alleviating the pressure on secondary and tertiary healthcare.

As we proceed along this course, there will inevitably be upfront investment on PHC, but that may delay and alleviate the healthcare burden on secondary and tertiary healthcare brought about by ageing population and thus slow down the rate of increase in secondary and tertiary healthcare expenditure in later years. The commitment will be contributed by government expenditure, investment from the society and the citizens towards their personal health, and optimisation of existing PHC resources towards more cost-effective PHC with better health outcomes. The result of reduction in health service utilisation and subsequently, reduction in costs for hospitalisation associated with related complications will only come into effect at later stage.

In consideration of the above, we propose the following to further enhance public-private collaboration and optimise the use of private healthcare resources to identify and support chronic patients, in order to release pressure on public specialist and hospital services –

Recommendation 4.1

Subsidisation for chronic disease screening and management

We have proposed in Recommendation 2.2 the introduction of a CDCC Scheme to enhance the chronic disease management role of the private PHC sector by providing subsidisation for chronic disease patients. The number of HA patients with at least one common chronic diseases is projected to reach 3 million in the coming decade by 2039. Through subsidising screening and management of targeted chronic diseases, we aim to achieve the target of early identification and appropriate intervention for these targeted patients at the community level in order to delay complications and alleviate the pressure on secondary and tertiary healthcare. We believe that the financing levers and incentives provided are in line with our intended healthcare goals and health system changes as evidenced by cost-effectiveness studies on chronic disease management service model as mentioned in paragraph 156 [20,21].

Local studies have shown the benefits and effectiveness of management of chronic disease at primary level in relieving healthcare burden. According to a local study on “Chronic Disease Screening Voucher and Management Scheme”, the health system will save about 28% or 12.5 billion on direct healthcare expenses over 30 years and prevent a total of 47 138 mortalities through the provision of subsidised screening and management services for DM management in the private sector for individuals between the ages of 45 – 54 years for DM and prediabetes [22]. In accordance with the results, it is envisaged that the economic savings for subsidized screening and management for both HT and DM for all age groups would result in even greater healthcare savings and prevention of mortalities. Local cost-effectiveness studies also demonstrate that multi-disciplinary intervention of DM and HT programmes would save up to $11,200 (or 38% of the original cost ($ 29,451)) and $6,000 (or 33% of the original cost ($18,312)) per patient per year, amount to 5% and 10% of the total annual cost on all HA’s services received by all HA patients in 2019/20 respectively [20, 21]. The cost reduction was driven by more effective preventive interventions at earlier stages of disease and more timely holistic treatment. The economic analysis also revealed that while initial investment of RAMP care is higher than usual care, the upfront cost is offset by the reduction in health service utilisation and subsequent reduction in costs for hospitalisation associated with related complications associated with these patients.

There will certainly be a number of variables affecting the final budget, for example, the number of current HA patients joining the private sector, the efficiency of identifying and screening at-risk individuals, and the market cost for HT and DM management which will be affected by market competition and induced demand brought about by the Government subsidy. In particular, the co-payment level from participating patients of the CDCC Scheme, and the corresponding level of Government subsidy, would directly affect the willingness to pay of individuals. An optimum co-payment level will be a crucial factor affecting the success of the CDCC Scheme. According to a local study on “Chronic Disease Screening Voucher and Management Scheme” by a local think tank, 56.2% of respondents were willing to pay at a range from $51 to $200 per consultation for the co-payment for chronic disease management [22]. In this connection, thorough research and programme design are required to achieve the intended healthcare goals and health system changes, especially due to the prevailing low price transparency of the private PHC sector.

Regardless of the above which will be subject to further studies and analysis upon detailed design of the Programme by the SPO (see Recommendation 4.3), it must be emphasised that the financing model of the Programme should be based on co-payment so as to encourage members of the public, as the manager of their own health, to bear part of the costs of the services. While co-payment is required for the Programme, GOPCs under Recommendation 2.3 will be repositioned to focus on services for the poor elderly and the low-income families. We believe that such an arrangement would achieve market segmentation and improve healthcare efficiency through a targeted, streamlined approach.

Recommendation 4.2

Reallocation of primary healthcare resources – the Elderly Health Care Voucher

The Government has implemented the EHCV Scheme since 2009. Currently, the Scheme subsidises eligible Hong Kong elderly persons aged 65 and over with an annual voucher amount of $2,000 (accumulation limit of $8,000). It adopts the concept of “money following the patient” which allows eligible individuals to choose private PHC services that best suit their health needs. The Scheme aims to enhance PHC for the elderly persons and provide them with an additional choice of service, thereby supplementing the existing public healthcare services and making it easier for the elderly persons to receive healthcare services from their chosen service providers. The estimated expenditure for implementation of the Scheme in 2022-23 is $4,375.8 million.

The EHCV Scheme utilises about 18% of the existing public PHC resources annually, after excluding COVID-related PHC expenditure. According to the comprehensive review of the EHCV Scheme in early 2019, the utilisation of EHCV is heavily skewed towards acute services rather than disease prevention or chronic disease management. Following the review, the Government progressively rolled out various measures to enhance the operation of the Scheme, including allowing the use of the vouchers at DHCs; strengthening education for the elders on the proper use of the vouchers and forward planning; enhancing the checking, auditing and monitoring of voucher claims; minimising over-concentration of voucher use, etc.

EHCV will continue to support the Government’s policy objective of promoting PHC, support elders’ health needs, assist to enhance their awareness of disease prevention and self-management of health, as well as complement the development of DHCs. On this premise, we will strive to ensure the optimisation of resources invested in the Scheme. In addition to considering the impact on public finances, we also need to ensure that the Scheme can effectively achieve the objective of promoting PHC. To achieve the PHC objective as set out in this Blueprint and finance part of the resources required for implementing Recommendation 4.1, it is proposed that the EHCV Scheme should be improved to direct resources towards PHC services with an emphasis on strengthening chronic disease management and reinforcing the different levels of prevention.

As covered in the 2022 Policy Address, we will roll out a three-year pilot scheme to encourage the more effective use of primary healthcare services by the elderly, increasing the annual voucher from the existing $2,000 to $2,500. The additional $500 will be allotted to their account upon claiming at least $1,000 from the voucher for designated primary healthcare services. The additional amount should also be used for those designated services. Going forward, the voucher user would need to register with a family doctor (which is listed on the PCR), in order for the use of vouchers with the family doctor concerned to be treated as a designated use. The goal is to encourage elders to make good use of their vouchers to choose PHC services for disease prevention and health management more effectively.

Apart from the above, we will continue to keep in view the operation of the Scheme and make appropriate adjustments and take suitable measures as necessary so that elders could make proper use of vouchers for their own health by choosing appropriate PHC services for disease prevention and health management.

Recommendation 4.3

Reallocation of primary healthcare resources – strategic purchasing of primary healthcare services

A carefully designed and balanced financing system, comprising government policies, safety net, healthcare vouchers, user co-payment, self-financing services, insurance, etc., would play an important role in driving towards an optimal healthcare system addressing the population’s healthcare needs. To achieve all these, strategic purchasing should come into play.

The Government intends to use strategic purchasing as a tool to complement Hong Kong’s existing dual-track healthcare system through bridging the segmented public and private sectors so that PPP initiatives could be procured and administered in a more strategic and holistic manner. It will help address priority duplications and service gaps between the public and private sectors, reduce service inefficiencies and mismatches, and ultimately bring about co-ordinated and integrated care to patients which would maximise their health benefits.

With strategic purchasing, a range of differential healthcare products in the form of strategic purchasing programmes (SPPs) having corresponding differential prices and subsidies between the two sectors will emerge, so that greater choices with better coverage and continuity of care could be offered to patients to suit their personal health needs, preference and affordability. The programmes or services should be reliable through accreditation and credentialing. At the higher level, a better balance between demand and supply of services, as well as between the public and private sectors could be achieved, which would contribute to the long-term sustainability of the healthcare system in Hong Kong.

Table 4.2

- To build better PHC systems

- To address pressure areas in the public healthcare system

- To address mismatch in supply and demand

- To contain health cost escalation

- To pool healthcare resources

- To better utilise healthcare resources towards better health outcomes

We have proposed in Recommendation 3.1 that the proposed Primary Healthcare Commission should be positioned to oversee the provision of PHC services, including service planning and resource allocation through strategic purchasing. With the setting up of the Primary Healthcare Commission, it should be tasked to look into the most efficient ways in delivering PHC which do not necessarily mean direct service delivery. On behalf of the Primary Healthcare Commission, the SPO will oversee the development and implementation of SPPs at primary care level, so as to channel resources more effectively towards PHC, reduce service duplications, gaps, inefficiencies and mismatches between the public and private sectors in PHC. A purchaser-provider split service delivery model should be adopted to bring about competition among providers and improvement in service delivery in terms of greater organisational flexibility and responsiveness of services to patient needs. Comprehensive and long-term vision should be formulated for more cost-effective use of public resources to meet healthcare needs and alleviate service burden of the public healthcare system.

Under the new role delineation between DH and the Primary Healthcare Commission, some of DH’s direct PHC services would be integrated into the Primary Healthcare Commission by phases. The Primary Healthcare Commission and the newly set up SPO will recommend the best approach on service delivery in these areas with a view to allowing more cost-effective provision of healthcare services while maximising population health. As a result, there should be room for the existing PHC resources to be reallocated more efficiently.

Table 4.3

Scope of Service of Strategic Purchasing Office(SPO)

Population-wide Programmes

- Population-wide Programmes are programmes that are designed on population-wide basis under defined scope of target providers and clients, aiming to achieve the Government’s healthcare policies and objectives.

- SPO will explore, plan, launch, administer, review and evaluate the programmes according to the programme policy objectives

- Partnership and synergy with DHCs under the Health Bureau and the CMCTRs would be

planned - In view of the fact that the resources of Hong Kong's CM sector are mainly concentrated in the private market, we will also explore enhancing CM PHC services by, inter alia, resource allocation through strategic purchasing.

HA Patient Programmes

- HA Patient Programmes are programmes that would cover HA patients only, aiming to achieve the Government’s objective of building an integrated healthcare system with respect to HA services.

- All existing HA PPP programmes will migrate to SPO by phases for management and administration

Elderly Health Care Voucher (EHCV) Scheme

- EHCV Scheme will migrate to SPO for management and administration

- SPO will leverage on the EHCV Scheme and other available financial resources to build incentives in the SPPs with a view to develop desirable health seeking and health providing behaviour toward targeted health outcomes for the population

Recommendation 4.4

Land resources for primary healthcare services

Aside from financial resources, another important angle in developing PHC is the availability of land resources. In the course of developing DHCs in 18 districts, one of the major hurdles encountered was to identify suitable space for the provision of services at the community level. Currently, responsibility for land inventory management, projection of demand in relation to public PHC facilities is scattered within DH and HA which may result in a lack of overview and overall co-ordination in planning, leading to sporadic if not haphazard development and use of premises, posing obstacles to long-term development and consolidation as well as sustained renewal of health facilities.

Apart from public healthcare facilities, we consider that land resources would be an important incentive for the development of PHC in the community, especially in terms of facilities planning for private or NGO PHC services. As opposed to secondary and tertiary care facilities which usually involve larger scale developments and comparatively smaller in number, and where convenience of location to local residents may not be a prime consideration, private or NGO primary care services are mainly accommodated in commercial premises or premises owned or rented by NGOs. The availability of affordable space could be a factor limiting the provision of accessible PHC services. We propose to pursue development and redevelopment of government buildings and premises for healthcare facilities at the community level and to examine the feasibility of providing accommodation space therein for certain private healthcare service providers or NGOs to provide PHC services, in order to facilitate their development as part and parcel of the district-based community health system, and the delivery of seamlessly integrated, co-ordinated and continuous PHC through co-location.

In tandem, for better planning and development of PHC service facilities, we propose to a clear delineation of the following tasks and roles on the management of health-related land resources under the proposed Primary Healthcare Commission:

- Redevelopment: Redevelop older Government buildings with outdated PHC facilities or in dilapidated conditions and maximise the development potential.

- Consolidation: Consolidate and co-locate PHC facilities at convenient locations including NGOs operated ones.

- Earmarking: Provide space for PHC facilities including private and NGO services under relevant or new policies to be formulated in support of PHC development.

- Synergising: Take into account the nature of health facilities that may benefit from co-location for synergies.

- Dovetailing: Dovetail with impending or possible service re-organisation plans, as well as other development or redevelopment programmes.

Chapter 4 - CONSOLIDATE PRIMARY HEALTHCARE RESOURCES: Action Plan

4.1 CDCC Scheme

To conduct market research and programme design for the CDCC Scheme

Action: Short

To review the positioning and interfacing of the GOPC PPP and the CDCC Scheme in terms of pricing, drug list, subsidisable conditions and referral criteria, etc.

Action: Short

To transition the GOPC PPP to the CDCC Scheme

Action: Short - Medium

To conduct ongoing review and evaluation on the CDCC Scheme

Action: Short - Medium - Long

4.2 EHCV

To review the applicability of ECHVs for other PHC programmes besides DHC

Action: Short

To designate a certain amount of Elderly Health Care Voucher for preferred use related to PHC purposes and self-registered family doctors

Action: Short - Medium

4.3 Strategic Purchasing Office

To set up the Strategic Purchasing Office (SPO) by integrating the existing Health Care Voucher Division of DH and Service Transformation Department (PPP office) of HA

Action: Short

To oversee the development and implementation of PHC programmes under strategic purchasing

Action: Short

To conduct ongoing review and evaluation on the SPPs

Action: Medium - Long

To explore enhancing Chinese medicine PHC services by resource allocation through strategic purchasing

Action: Medium - Long

To set up the community drug formulary to support patients.

Action: Short - Medium - Long

4.4 Land resources

To set up a centalised inventory of healthcare facilities to identify and project supply-demand gap of land resources for PHC services

Action: Short

To explore room to consolidate and co-locate health service facilities especially those relating to PHC services

Action: Short - Medium

To devise a policy for land premium concession by non-profit making organisations delivering PHC services

Action: Short

To explore providing space for PHC facilities for the use of healthcare operators (including those to be operated by NGOs) under relevant policies

Action: Medium